Swollen Parts

"The Extraordinary with the Usual"

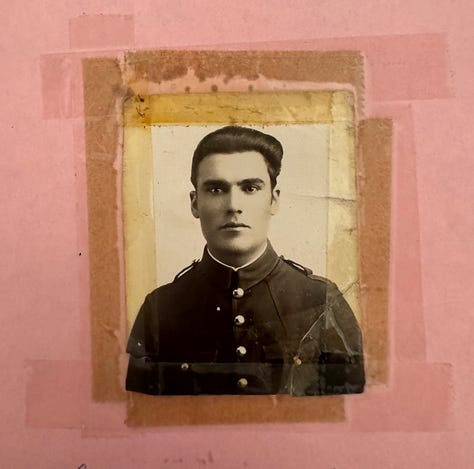

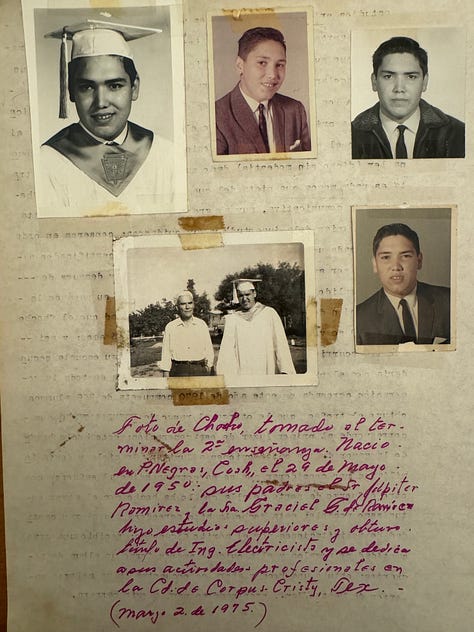

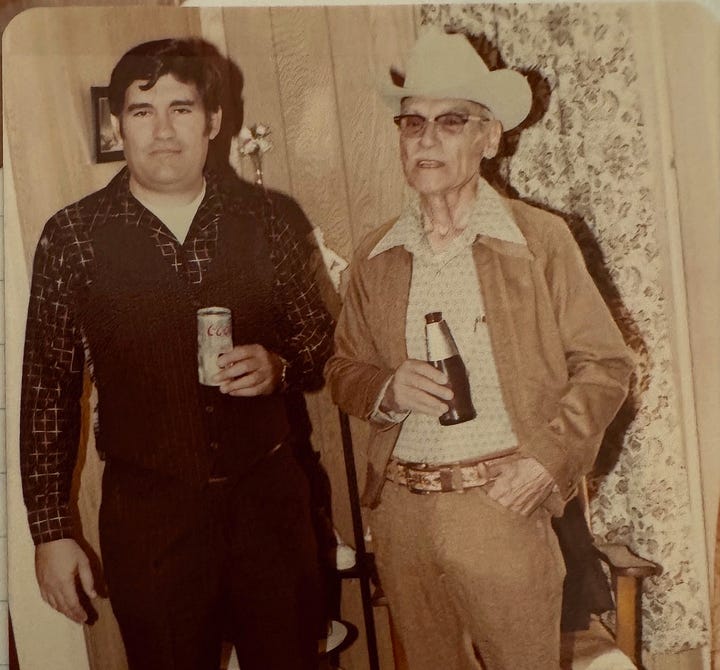

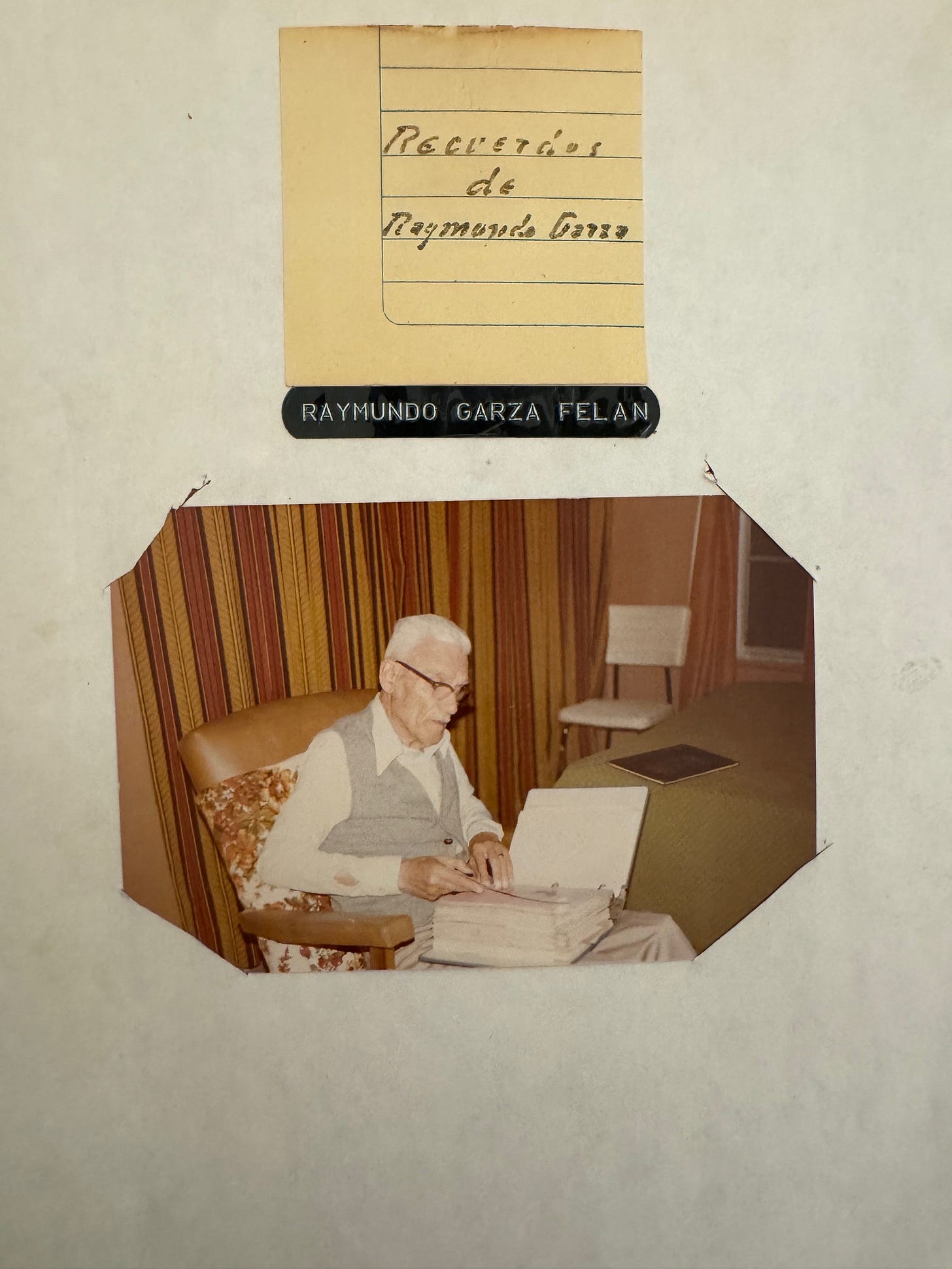

My aunt gave me my great-grandfather Raymundo Garza Felan’s memoir several months ago, and receiving this gift has been a highlight of my year. Raymundo was an incredible man – a thoughtful, Spartan, and organized gentleman with a good sense of humor. He was my father’s grandpa, and they shared a bedroom in my grandparents’ home in Eagle Pass, Texas when Raymundo retired in the ’60s.

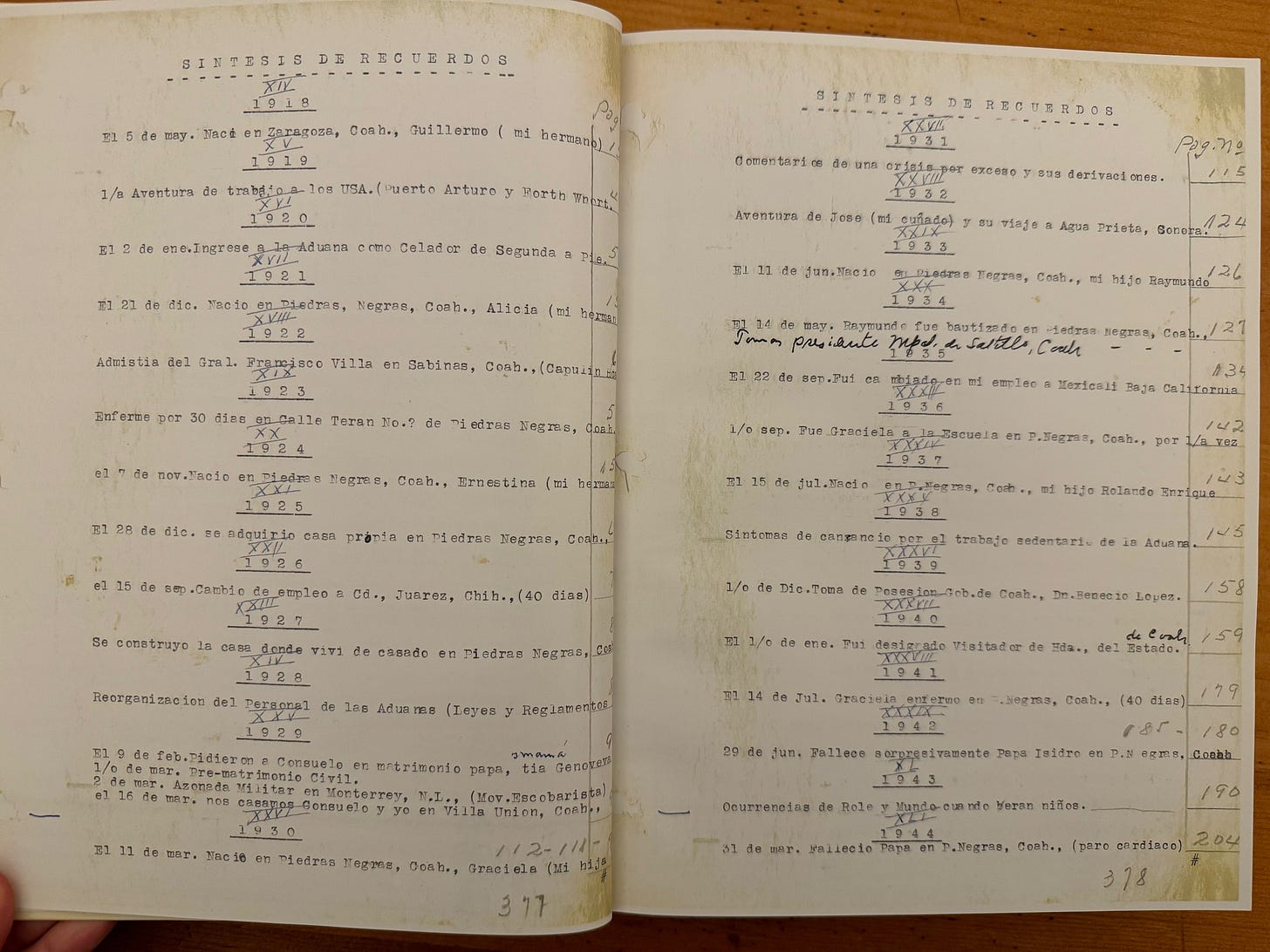

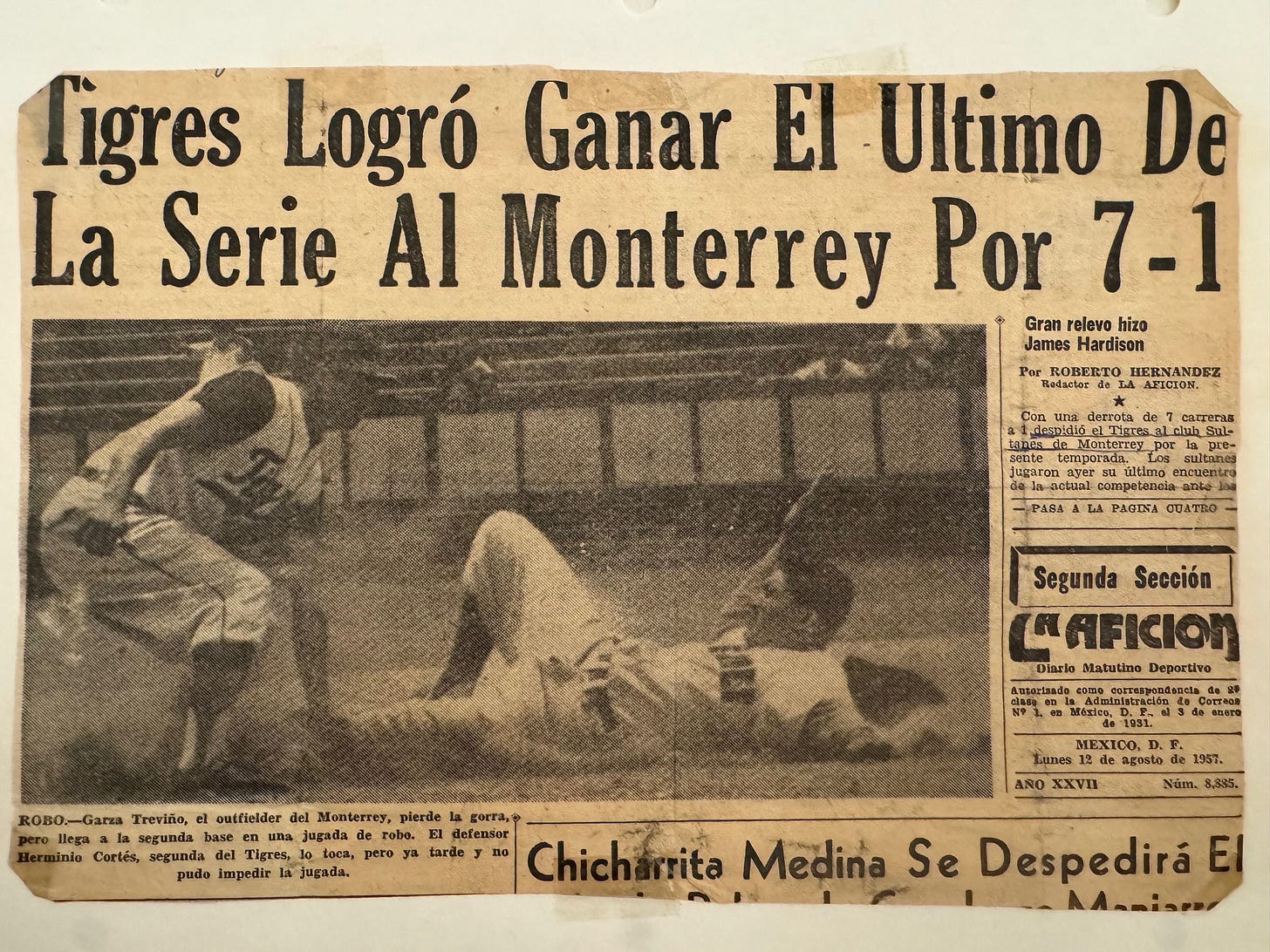

The memoir is nearly 500 pages long, organized into four sections: childhood, youth, middle age, and retirement. It juxtaposes photos, newspaper clippings, letters, wedding invites, certificates, and other ephemera with typed pages that chronicle his life from 1902 to 1975. It even has an appendix and a table of contents. He pulled everything together in a fat binder with page protectors and dedicated the tome to his children. At some point, my aunt made black-and-white copies to share with all of her cousins – but the quality was lacking in sections. I decided to make color copies for the next generation and have been handing them out to relatives in Mexico and the US this fall.

I’m slowly reading through my copy and it’s beautiful. Raymundo wrote about his life growing up in Coahuila and seeing his father join the Mexican Revolution; going to Gary, Indiana for work; and then, randomly, the effects of peyote (based on an article he read about the native plant). There’s a section dedicated to his wife, who died at 39, that had me in tears: “The memory of the greatest love of my life lived, lives, and will live within the most intimate part of my being until my life runs out.”

I’m learning that Raymundo and I share a lot of qualities in common, and I’m looking forward to finishing the book over the next few months. For now, I’ll leave you with the foreword he wrote on October 31, 1975:

These notes are… a diagnosis (or complementary balance) of personal history.

These pages mix the important with the less important – the extraordinary with the usual, the unforgettable with what is easily forgotten – in the same way that time and life mixed them.

What could be considered a pretension is nothing more than precision and accuracy… The triumphs, the family (or whatever these things are called) are morality in itself, which when fused with life, prevents us from remaining faithful to our youth.

Every historical reflection implies correction and adjustment of diverse situations in life. I hope that this work will serve to clarify events (which have not yet been sufficiently understood), and demonstrate my attitude to them.

Today I only live off my memories.

Kissed by a Snake

Last week I hosted our marketing team’s all-hands meeting and, as customary to the agenda, I gave my introduction with a fun fact: “I was bit by a snake while I was a Peace Corps Volunteer.”

After sharing my fact, the Google Meet screen filled up with tons of reacjis. “Clarisa - EPIC!” a friend wrote the comments. The CMO stopped me before I went to the next slide and said, “You can’t just leave us with a cliffhanger!” Unfortunately, I didn’t have time to elaborate but I told the group I’d fill them in later. And then I realized that the story needed to be shared here because it is a good one. Here’s a revised version of what I wrote about the incident for our Peace Corps magazine in 2010.

It was dusk and I was running errands around my Peace Corps village, making my way up a steep road to a grocery store. I stopped a man I knew on the road, Milo, to see if he wanted to buy a copy of the newsletter my counterpart and I published and we struck up a conversation.

“Wow, you’re really sweating,” Milo said.

“Oh, you know gringos sweat more than Costa Ricans,” I said.

“Why is that?” he asked. “And where are you going?”

Right when I began to answer, I felt a prick on my foot. I yelped and the man looked at me with a blank expression. He had no idea what was going on. “Something bit me,” I explained. I took off my shoes and noticed two tiny red marks on the right-hand side of my foot, between my ankle and my smallest toe. Two seconds later, Milo spotted the small, bright green snake a couple of meters away from me. I had stepped on it by mistake.

“There it is!” The snake was just two meters away from us, making its way back into the coffee field. Milo trampled it with his boots. Then he asked me if I wanted him to suck out the poison. I thought he was going to cut my foot open with a knife, so I said no. I was bawling like a baby. “I’m taking you to the clinic in San Marcos,” he said. From there, I would go to the next biggest city, Cartago, by ambulance.

We brought the the dead snake, a lora, with us in a plastic bag so the medics could give me the right anti-venom. I was still crying until Milo said, “Calm down. You are not going to die.” He said the same type of snake bit him and all he did was drink two cups of banana vinegar and that was it. Of course, his foot swole up for about a week – but he didn’t have to go to the hospital. I collected myself.

Everybody asks about the pain. Getting bit by a snake is initially no worse than getting bit by a bee. The throbbing catches up with you later. You feel like your veins have lead inside of them. The pain comes in waves as the venom moves farther up your body, and then you kind of get used to it, and then it crawls up again.

When I arrived at my house to get my passport, I was still able to walk and my host family didn’t believe what happened until they saw the bite marks. My host mother told my host sister, Rebeca, to go with me. My host father would meet us in Cartago.

Milo, Rebeca, and I arrived at a nearby clinic in 30 minutes, they gave me an IV, and then put me in an ambulance. Through the ambulance windows, I could see cars passing us until we got to the emergency room.

People were outside waiting for hours to get into the hospital. Almost all of the beds were taken, and nobody talked to me until I was placed on one. I was connected to an intravenous solution and then to the anti-venom. I was given shots for the pain, the inflammation, and the infection; and then a nurse took about a quart of my blood. The nurse kept bossing Rebeca around, telling her to get her various forms and to talk to the doctor. The scene was chaotic, just like you see on TV, but none of the staff were running around. They were just walking casually, greeting each other and saying things like, “You want to get some coffee?” Everyone working there wrote on loose scraps of paper and stuffed the information in a folder under the corner of my mattress. The dead snake in the plastic bag remained under my bed.

I had to pee – but every time I asked a nurse or doctor for something it was like I was killing their buzz. I had to vary it from person to person or else they’d say, “That’s not my job.” When I finally did get my hands on a bedpan, I peed in front of 20 people with only a sheet wrapped around me for privacy. But nobody paid attention because the majority of my neighbors were passed out.

I called the Peace Corps office, hoping they could transfer me to the fancy private hospital in San Jose. No dice. The Peace Corps doctor, Sonsire, assured me it was a good enough place because the treatment for snake bites like mine is the same everywhere. Also, her husband worked there as a gynecologist.

I had to stay until my blood results were evaluated. Some people have allergic reactions to the anti-venom, so I’d have to be on watch for 24 hours. I was starving so I asked for some food. The nurse laughed at me: “We already served dinner,” and he gave me a packet of crackers. I decided to stare at the nurse for the rest of the night until he attended to my other requests: a cup of water, a shot for the pain, a fresh bedpan, and an allergy tablet.

“Why didn’t you bring your allergy pills with you?” he asked.

“I didn’t think I would be spending the night in the ER,” I replied. Really?!?

You can’t sleep in an emergency room like the one I was in without heavy drugs. People were moaning all night long and the beds weren’t comfortable. There weren’t any rooms or curtains; and all of the beds were placed side by side, as if we were all in a big sleepover for miserable people.

I was sent to the showers the next morning. Someone gave me half a bar of hotel soap and a hose to bathe myself on a plastic chair. I assured the supervising nurse that I didn’t need any help. Taking a shower was the highlight of my morning.

There was no TV, music, or magazines. I spent hours reading and rereading the text in my passport. Out of desperation to do something, I befriended my neighbor – an elderly, diabetic man suffering from gangrene. His toes were cut off the week before and he needed to get more cut off. His foot resembled a square piece of steak with a black mark on it. He was unexpectedly chipper about the whole thing and excited about getting surgery.

“I’m going up!” he told me as the nurses made plans to wheel his bed away. “They serve food up there and people can stay with you. Best of luck!”

My new neighbor was not as engaging. I learned from an assistant that she was 82, lived in a boarding house, sprained her ankles, had diabetes, had no teeth, had no family, suffered from Alzheimer’s, and was being treated for an extremely infected vaginal infection. She howled like a wild cat every so often. I felt so bad for her.

Other patients included a domestic abuse victim with two black eyes, a homeless man who drank too much and smelled like he hadn’t bathed in years, and a woman suffering from a heart attack. I was probably the only patient craving a stick of gum.

One guy came in high on pills. While his mother was talking to the doctor he stared right at me and asked what was wrong with me. When I explained what happened, he started to wave his hand over my foot. “Don’t touch it,” I told him. The jerk touched it.

“Let me give you some advice,” he told me. “If you have the money, you should buy yourself a car. Capiche?” Minutes later, I heard him getting his stomach pumped while his mom repeatedly called him a “spoiled brat.”

Peace Corps staff came to visit me and brought me lunch: chicken drenched in a red, sticky-sweet sauce, beet salad, French fries, and a plastic teaspoon – the kind you sample ice cream with. I asked no one, “Can I get some napkins?” I caught the attention of the security guard but he told me it wasn’t his job. I ended up wiping my hands on the already yellow-stained sheets.

My second round of anti-venom came shortly after their visit. I read my clinical papers, still stuffed under the mattress, and noticed the doctor wrote, “We don’t have more medication.” I asked the doctor when I was going to leave. He looked at me for a few seconds, looked away, and said, “You’ll be staying the night again.” I didn’t see him after that. When the rush hour came through, I was pushed out of my corner and into the middle of the room. Finally, Sonsire came in at around 7 p.m. with her husband and another doctor, who were both wearing lab coats. Their presence quickened the process of getting me out. All I had to do was take three types of medication at home for a week. I was feeling fine but when I attempted to get off the bed my foot, swollen at the ankle, couldn’t move. Every time I put my foot down it throbbed. It felt hot and tender like a baked potato, and my ankle felt like it was 9 months pregnant.

When I was back in my village, I kept my foot up and bathed it with milky liquid that reduced the swelling. The villagers came by to visit and share their own snake horror stories, and I realized the experience gave me street cred.

A few days later, I was back on my feet and I thought the worst was over. Then, exactly a week after the accident, I broke out in an intense rash that made my knees, elbows, ankles, and wrists red, puffy, and itchy. Most anti-venoms come from a horse so your body breaks out in response to the animal’s antibodies. So, I went to a private hospital and was prescribed anti-inflammatory medicine and allergy pills.

That night I was in excruciating pain. My ears, neck, face, back, and shoulders were burning. It felt like my blood was boiling and little pins were poking out of my skin. I was hot to the touch and there was nothing I could do but rub burn cream all over my skin. The rash moved throughout my body; one day it’d be all over my legs and then next it’d be on my chest and my arms.

“Give it a couple of days,” my host father said as I rested in bed, oily from all of the cream and crying like a pathetic baby. He was right. In fact, after 48 hours I had more energy and enthusiasm than I had for a long time. And now I’m forever remembered in the village as the gringa who got bit by a snake.

Ten things you should do this fall

Go on a walk under the full moon

Dance in your room for 15 minutes

Write down your dreams when you wake up

Listen to music while taking a bath

Send a friend a postcard from your hometown

Draw a three-panel comic about a funny mishap

Primal scream in your car after work

Read my friend’s AI-generated lists and make your own here

Host an elaborate tea party instead of going out to brunch

Read my past posts here

Wow. That forward by your great grandfather is epic! You are both great writers. An excellent excerpt for the title. Love the snake story too. What an experience!

This was so lovely to read! I’m glad you shared it 🙂